Tutorial Categories

Last Updated: January 15, 2026 at 10:30

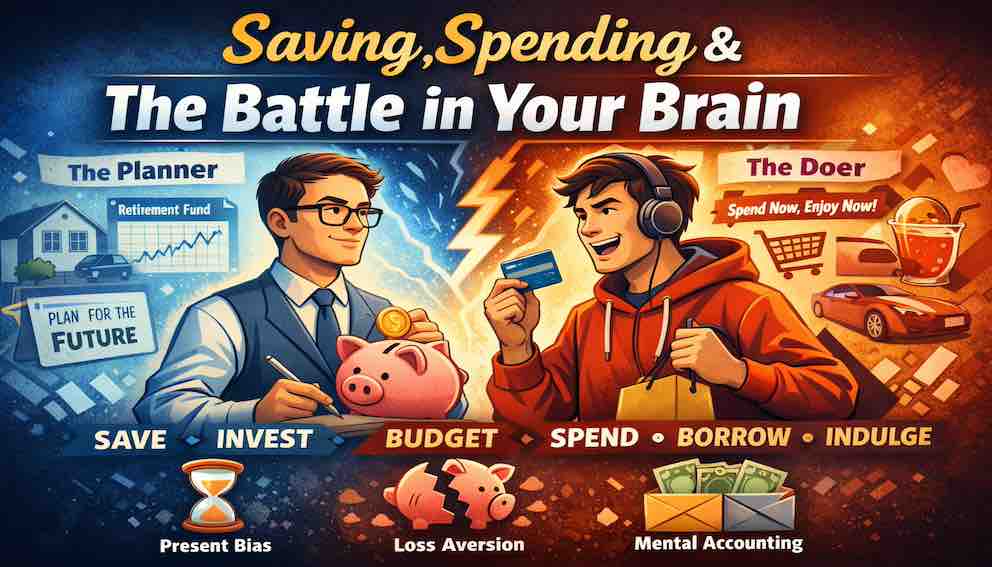

How Biases Affect Saving, Spending, and Debt - Behavioral Finance Series

Ever plan to save or invest, but end up spending on small treats or gadgets instead? That’s your brain at work. Your long-term “Planner” wants financial security, but your short-term “Doer” craves instant rewards. Behavioral biases like present bias, loss aversion, and mental accounting quietly steer your choices—even when you know better. The good news: You can design your financial environment to work for you. Automate savings, pre-commit future income, use cooling-off rules for big purchases, and track progress visually. With the right systems, your Planner wins without relying on willpower alone. Try this: Look at your last three spending decisions. Which impulse might have influenced them? How could a simple rule or habit have helped?

Picture this: You get a $1,000 bonus at work. Your Planner self thinks: “Save this for retirement.” Your Doer self thinks: “I deserve that new gadget I’ve been eyeing!” You buy the gadget. A week later, you feel some regret, but when your next paycheck arrives, the cycle repeats.

This tug-of-war is at the heart of most personal finance struggles. Behavioral biases quietly push us toward spending, under-saving, or accumulating debt. Understanding why this happens—and how to design your financial environment—is the key to winning the battle between your immediate impulses and your long-term goals.

Core Theory: The Planner-Doer Model

At the heart of our financial struggle is what behavioral economists Richard Thaler and Hersh Shefrin called the Planner-Doer conflict.

- The Planner (System 2, long-term self): Wants to save for retirement, build emergency funds, and achieve financial security.

- The Doer (System 1, short-term self): Craves immediate gratification, wants to spend now, and underestimates future needs.

Most personal finance failures occur when the Doer wins. Behavioral biases are the Doer’s tools:

- Present Bias makes future rewards feel trivial.

- Mental Accounting creates “spendable” buckets of money.

- Loss Aversion makes cutting expenses feel painful.

The Planner can’t fight the Doer by willpower alone—systems, rules, and commitment devices are essential tools to tip the scales in favor of long-term goals.

Key Behavioral Biases Affecting Money

1. Present Bias / Hyperbolic Discounting

We overvalue immediate rewards and undervalue future benefits.

Example: A 25-year-old investor postpones retirement contributions because $500 today feels like a loss, while the benefit of compounding decades later feels abstract.

Financial Consequence: Chronic under-saving, missed employer matches, and weak emergency funds.

Mitigation:

- Automate contributions to savings or retirement accounts.

- Use Save More Tomorrow (SMarT) programs: commit a portion of future salary increases to savings—makes the “loss” feel delayed, reducing friction.

- Try temptation bundling: link a pleasurable activity with a productive one (e.g., only listening to your favorite podcast while budgeting).

2. Loss Aversion

We feel losses more intensely than equivalent gains.

Example: Jane avoids cutting her daily coffee habit to pay down $8,000 in credit card debt because giving up coffee feels like a real loss.

Financial Consequence: Debt grows, savings stagnate, and small spending habits quietly undermine wealth building.

Payment Method Effect: Modern payments weaken this natural brake. Paying with cash triggers real psychological pain, but credit cards, digital wallets, and “buy now, pay later” remove it, encouraging overspending.

Mitigation:

- Reframe losses as future gains (“Skipping coffee now builds freedom later”).

- Use cooling-off rules for large purchases (e.g., wait 48 hours before spending >$300).

3. Mental Accounting

We often divide money into buckets—some for spending, some for saving—rather than treating all funds as fungible.

Example 1: A retiree treats dividends as “income to spend” and capital gains as “capital to preserve,” leading to overconcentration in safe, low-growth assets.

Example 2 (Windfalls & Flypaper Effect): Tax refunds or bonuses are mentally earmarked for spending, not saving, sticking to consumption like flypaper.

Financial Consequence: Misallocated resources, overspending, and underinvestment in high-return opportunities.

Mitigation:

- Treat all money as fungible, or consolidate windfalls into general savings or debt repayment.

- Rules-based budgeting: allocate fixed percentages for necessities, discretionary spending, and savings.

4. Optimism Bias & Overconfidence

We tend to overestimate future income and underestimate risk.

Example: A young professional assumes a promotion will arrive soon and takes a car loan they can barely afford. When the promotion is delayed, payments become stressful.

Financial Consequence: Stretching budgets, increased debt, and financial anxiety.

Mitigation:

- Scenario planning: model worst-case outcomes before major expenses.

- Cooling-off rules and reflective spending decisions.

5. Social Proof & Status Quo Bias

We follow what peers do or stick with familiar habits, even when suboptimal.

Example: Tom keeps an expensive cable subscription because friends have it. Maria keeps a basic checking account because her family always did.

Financial Consequence: Persistent unnecessary expenses and avoidance of better options.

Mitigation:

- Join communities with healthy financial habits.

- Introduce accountability partners to reinforce good behavior.

- Evaluate habits critically: just because “everyone else” does it doesn’t make it smart.

6. Debt Aversion (Sometimes Harmful)

Some people irrationally avoid productive debt, like mortgages or student loans, due to exaggerated fear of owing money.

Financial Consequence: Missed opportunities for wealth building, slower career or education advancement.

Mitigation:

- Educate yourself on interest rates, loan returns, and long-term benefits.

- Consider low-interest, strategic debt as an investment, not a liability.

Financial Consequences in Everyday Life

- Credit Card Debt: Present bias + optimism = overspending and deferred payments. Interest compounds quickly.

- Payday Loans: Short-term relief, long-term pain, fueled by present bias and loss aversion.

- Retirement Procrastination: Mental accounting and present bias reduce early contributions, limiting compounding benefits.

- Impulse Buying: Social proof + optimism bias = unnecessary spending, less available for savings or debt repayment.

Expert vs Novice Approaches

Novice investors tend to act sporadically and reactively. They save only when they feel like it, spend impulsively, often influenced by friends or social trends, and manage debt reactively—sometimes relying on high-interest credit or payday loans. Reflection is rare; decisions are often followed by regret rather than thoughtful review.

Experts, by contrast, take a process-driven approach. Savings are automated and rules-based, ensuring consistent contributions regardless of mood or temptation. Spending is deliberate, pre-committed, and reflective, guided by budgets or pre-defined limits. Debt is handled strategically, prioritizing high-interest balances and avoiding unnecessary borrowing. Reflection is routine, with regular reviews of progress and adjustments to plans as needed.

Example: Instead of deciding each month how much to save, an expert sets up an automatic transfer of 15% of their income to a retirement account. The Doer cannot intervene—automation enforces the Planner’s plan and keeps long-term goals on track.

Mitigation Strategy for Key Biases

Several behavioral biases can subtly influence how we save, spend, and manage debt, but understanding them allows us to take practical steps to counteract their effects.

Present Bias makes us favor immediate rewards over future benefits, which often leads to under-saving or procrastination. To overcome it, automate your savings, use programs like Save More Tomorrow to commit future raises to retirement, or try temptation bundling by pairing enjoyable activities with financial tasks.

Loss Aversion causes us to avoid spending cuts or debt repayment because giving up something now feels painful. Counter this by reframing sacrifices as investments in your future freedom and applying cooling-off rules for large purchases.

Mental Accounting can make us treat money in different “buckets,” such as spending windfalls like tax refunds instead of using them to pay down debt or increase savings. The solution is to treat all money as fungible, consolidating windfalls into general savings or debt repayment, and using rules-based budgeting to guide allocation.

Optimism and Overconfidence lead us to overestimate future income and underestimate financial risks, which can result in overspending or taking on debt we cannot manage. Mitigation strategies include scenario planning for worst-case outcomes and applying cooling-off periods before major purchases.

Social Proof and Status Quo Bias push us to spend like others or maintain familiar, suboptimal habits. We can combat this by seeking positive financial communities, having accountability partners, and consciously evaluating whether habits and expenses truly serve our goals.

Debt Aversion, in some cases, makes people avoid productive, low-interest debt, such as mortgages or student loans, due to exaggerated fear of owing money. Education about interest rates and the long-term benefits of strategic borrowing can help turn debt into a tool for wealth building.

By understanding these biases and taking deliberate steps, you can create systems that favor your long-term goals, reduce impulsive behaviors, and make wise financial decisions easier to follow.

Nuance and Adaptive Aspects

- Evolved Heuristics: These biases likely helped ancestors survive scarcity (seek immediate rewards, follow the tribe). Modern financial systems (retirement accounts, compound interest) are a mismatch for these instincts.

- Financial Anxiety: Loss and regret aversion can sometimes freeze people into inaction—they avoid bills or checking accounts altogether. Recognizing this is critical to breaking the cycle.

Takeaway: These biases are not personal failings. The challenge is not perfect rationality—it’s architecting your environment and routines so the Planner wins more often than the Doer.

Reflective Prompts

- Look at your last three financial decisions. Which biases influenced them?

- Could a system—automation, rules, or a commitment device—have improved the outcome?

- Which “windfall” money can you allocate differently to build wealth or reduce debt?

About Swati Sharma

Lead Editor at MyEyze, Economist & Finance Research WriterSwati Sharma is an economist with a Bachelor’s degree in Economics (Honours), CIPD Level 5 certification, and an MBA, and over 18 years of experience across management consulting, investment, and technology organizations. She specializes in research-driven financial education, focusing on economics, markets, and investor behavior, with a passion for making complex financial concepts clear, accurate, and accessible to a broad audience.

Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes only and should not be interpreted as financial advice. Readers should consult a qualified financial professional before making investment decisions. Assistance from AI-powered generative tools was taken to format and improve language flow. While we strive for accuracy, this content may contain errors or omissions and should be independently verified.