Last Updated: January 18, 2026 at 18:30

When Good Decisions Have Bad Outcomes - Behavioral Finance Series

Most investors believe good decisions always lead to good results. Markets constantly prove the opposite. This tutorial explains why smart, disciplined decisions can still lose money, while reckless behavior is often rewarded in the short run. Using examples from the dot-com bubble, the 2008 financial crisis, and the 2020 crash, it shows how outcome bias distorts judgment, why experts focus on process instead of prediction, and how long-term success depends on emotional endurance, risk control, and survivability—not being right every time.

The Uncomfortable Paradox at the Heart of Investing

Let’s start with a situation almost every investor experiences.

Two people invest money at the same time.

- Investor A does careful research, thinks about risk, diversifies, avoids leverage, and accepts modest returns.

- Investor B follows excitement, concentrates bets, ignores risk, and chases what’s already going up.

For a while, Investor B looks like a genius.

Investor A looks slow, cautious, maybe even “out of touch.”

Then markets change.

Investor B suffers large losses.

Investor A survives—and keeps going.

Now comes the tricky question:

Who actually made the better decisions?

Most people answer this by looking at what happened after.

Markets do not work that way.

This tutorial is about one of the hardest lessons in investing:

A good decision can lead to a bad result.

A bad decision can lead to a good result—especially in the short run.

Understanding this difference is what separates:

- long-term investors from gamblers

- professionals from beginners

- discipline from emotional reaction

Outcome Bias and “Resulting”: The Core Mental Error

Humans naturally judge decisions by results.

- If you made money → it must have been a good decision

- If you lost money → it must have been a bad decision

This is called outcome bias.

Poker champion and decision-making expert Annie Duke gave this tendency a clearer name: “resulting.”

What is Resulting?

Resulting means judging the quality of a decision only by how it turned out.

In investing, this is extremely dangerous because:

- Markets are uncertain

- Outcomes contain a lot of randomness

- Luck can dominate skill for long periods

A beginner asks:

“Did this investment make money?”

An experienced investor asks:

“Was this decision reasonable given what I knew at the time?”

Those are very different questions.

A Simple Decision Matrix: How Experts Think

To make this clearer, experts separate decisions into two dimensions:

- Process quality (good or bad reasoning)

- Outcome (good or bad result)

| Good Outcome | Bad Outcome | |

| Good Process | Deserved success (skill + some luck) | Bad beat (skill + bad luck) |

| Bad Process | Dumb luck (luck hides a mistake) | Poetic justice (bad thinking + bad luck) |

What experts focus on

Experts try to maximize the top row: good process.

They accept that:

- Some good decisions will lose money (bad beats)

- Some bad decisions will look successful for a while (dumb luck)

What novices focus on

Novices focus only on the left column (good outcomes).

They often mistake:

- Dumb luck for skill

- Short-term success for intelligence

This confusion is how bubbles are born.

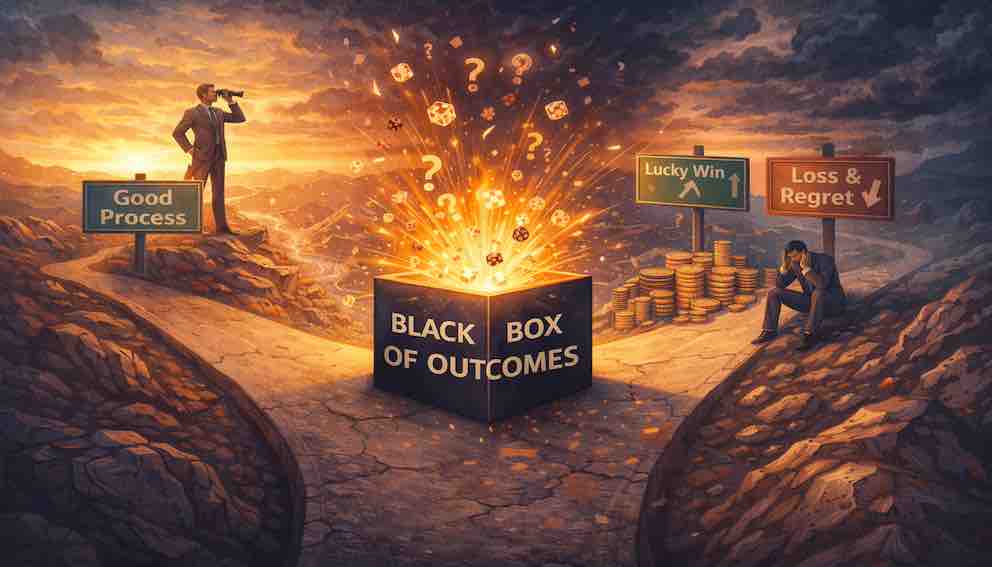

The Black Box of Outcomes: Why Judging by Results Is Illogical

A powerful mental model used by experienced investors is to imagine a Black Box between decision and outcome.

What goes into the box

- Your research

- Your assumptions

- Your risk controls

- Your position size

- Your reasoning

What’s inside the box

- Other investors’ actions

- News and narratives

- Central bank decisions

- Economic shocks

- Regulations

- Human emotion

- Randomness

You do not control what happens inside the box.

You only control what you put in.

Judging yourself by the output—something you don’t control—is logically flawed.

The only fair evaluation is of the decision process at the time it was made.

Skill, Luck, and Time: Why Markets Feel Unfair

Every market outcome is a mix of:

- Skill

- Luck

- Time horizon

In the short term

- Luck dominates

- Noise is high (Daniel Kahneman calls this “noise”)

- Risk-taking is often rewarded

- Careful thinking can look wrong

In the long term

- Luck evens out

- Bad processes compound into failure

- Good processes quietly assert themselves

Markets are not fair every year.

They are fair over decades.

Historical Example #1: The Dot-Com Bubble (1999–2002)

What felt right in 1999

- Buying internet stocks with no profits

- Ignoring valuations

- Believing “this time is different”

Stories dominated logic.

Who looked foolish

- Investors who avoided tech stocks

- Those holding cash

- Those talking about valuation and risk

For nearly two years:

- Rational caution underperformed

- Speculation was rewarded

Then reality arrived.

- Nasdaq fell ~78%

- Many companies went to zero

- Survivors were those who avoided permanent loss

Key lesson:

Avoiding overpriced assets in 1999 was a good decision, even though it felt wrong at the time.

Historical Example #2: The 2008 Financial Crisis

Before the crash

Some investors:

- Understood leverage risk

- Questioned housing assumptions

- Reduced exposure

- Bought insurance

- Accepted lower returns

They were mocked for being “too conservative.”

Others:

- Used leverage

- Trusted flawed models

- Assumed diversification meant safety

- Earned higher short-term returns

After the crash

- Cautious investors survived

- Aggressive investors collapsed

- The same decisions that looked wrong suddenly looked obvious

But hindsight hides the truth:

The skill was not predicting the crash.

The skill was surviving uncertainty.

Historical Example #3: March 2020 (COVID Crash)

During the crash:

- Fear felt rational

- Selling felt responsible

- Buying felt reckless

Some investors sold everything.

Others rebalanced calmly.

In hindsight:

- Buying was rewarded

- Selling was costly

But here’s the nuance:

Buying was not “right” because it worked.

It was right because it followed a disciplined process under uncertainty.

Expert vs Novice Reactions

Novice thinking

- “I lost money, so I was wrong”

- “This strategy doesn’t work”

- Frequent strategy changes

- Emotional decision-making

Expert thinking

- “Was my reasoning sound?”

- “Was risk sized correctly?”

- “Is this within expected outcomes?”

- Patience with temporary pain

Experts do not expect certainty.

They expect variance.

The Expert’s Burden: Emotional Endurance

Understanding that good decisions can have bad outcomes is only the first step.

Living with that reality is much harder.

In markets, being rational does not mean being comfortable.

In fact, rational investing often feels emotionally wrong.

Experts don’t just think differently—they endure differently.

Why Emotional Endurance Is Required

Markets provide constant feedback in the form of prices and profits.

That feedback is loud, public, and emotionally charged.

When a decision leads to a bad outcome:

- Your portfolio reflects it immediately

- Others can see it

- Your confidence is tested

- Your identity as a “competent investor” feels threatened

The temptation is to assume:

“If this feels bad, it must have been a mistake.”

Experts learn that this instinct is unreliable.

1. Normalizing Regret: Accepting the Cost of Rationality

Regret is unavoidable in investing.

You will:

- Miss bubbles that later look obvious

- Avoid trades that go on to succeed

- Make prudent decisions that lose money anyway

For beginners, regret feels like proof of failure:

“If I were smarter, I wouldn’t feel this.”

Experts see it differently.

They treat regret as:

A normal cost of making disciplined decisions under uncertainty—not a signal that the process is broken.

Just as insurance has a premium, rational investing has an emotional cost.

If you never feel regret, it often means:

- You are chasing outcomes

- You are taking excessive risk

- You are letting narratives guide decisions

Experts don’t eliminate regret.

They expect it and budget for it emotionally.

2. Managing Narrative Pressure: Standing Against the Story

After a bad outcome, something else happens.

A story forms.

- The media explains why the outcome was obvious

- Commentators connect dots that weren’t visible before

- Peers ask, “Why didn’t you see this coming?”

- Your own mind starts rewriting history

This is narrative pressure.

It pushes you toward:

- Self-blame

- Abandoning a sound process

- Changing strategies at the worst possible moment

John Maynard Keynes described this experience as:

“The inevitable torture of maintaining discipline.”

Why torture?

Because discipline often means:

- Looking wrong while others look right

- Holding steady while narratives shift

- Trusting a process that offers no immediate validation

Experts understand that markets reward conformity in the short run and punish it in the long run.

They accept that part of doing the right thing is:

Being misunderstood for longer than feels reasonable.

3. Solomon’s Paradox: Creating Emotional Distance

One of the strangest things about human judgment is this:

We are often wiser when judging other people’s decisions than our own.

This is known as Solomon’s Paradox.

When you lose money:

- Emotion dominates

- Self-criticism intensifies

- Outcome bias creeps in

When someone else loses money:

- You evaluate the reasoning

- You consider uncertainty

- You acknowledge bad luck

Experts deliberately use this gap to their advantage.

A simple but powerful tool

They ask:

“If a respected investor made this exact decision, with the same information, would I call it stupid just because it lost money?”

If the answer is no, then:

- The decision likely deserves respect

- The outcome was noisy

- The lesson is about uncertainty, not incompetence

This mental shift creates emotional distance between:

- The decision

- The outcome

- The ego

That distance is what allows learning instead of self-destruction.

The Key Rule Experts Live By

Experts follow a rule that beginners rarely articulate:

- Judge your decisions at the moment they are made,

- with the information you had and the process you followed.

- Judge outcomes only for what they teach you about uncertainty—

- not for what they say about your intelligence.

This rule is simple.

Following it is emotionally demanding.

Why This Matters More Than Intelligence

Most investors don’t fail because they lack knowledge.

They fail because they cannot emotionally tolerate being right too early, too quietly, or too painfully.

Emotional endurance is not optional.

It is the price of:

- Process discipline

- Probabilistic thinking

- Long-term compounding

Academic Foundations (Simply Explained)

Investing is not just about following rules or gut feelings. Behavioral finance sits at the intersection of psychology, economics, and complex systems. To make sense of why rational decisions sometimes fail, it helps to understand key academic concepts.

Here’s a guide to the foundational ideas, explained simply:

1. Outcome Bias (Baron & Hershey, 1988)

Definition: Judging a decision by its outcome rather than the quality of the process that led to it.

Example:

- Two investors make the same thoughtful, well-reasoned bet on a stock. One loses money due to market randomness, the other gains.

- Most people conclude the winner was “smart” and the loser was “wrong,” even though both made equally good decisions at the time.

Why it matters:

Outcome bias is the core error in result-based thinking. It’s what leads investors to chase recent winners, abandon sound strategies after a temporary loss, and confuse luck with skill.

2. Hindsight Bias (Fischhoff, 1975)

Definition: The tendency to see past events as predictable, or “obvious,” once they have occurred.

Example:

- After the 2008 financial crisis, many said, “It was obvious the housing bubble would burst.”

- In reality, very few investors predicted the timing and magnitude beforehand.

Why it matters:

Hindsight bias strengthens overconfidence and outcome bias. It tricks investors into thinking outcomes were inevitable, discouraging reflective learning and leading to poor risk assessment.

3. Noise (Daniel Kahneman, 2021)

Definition: Random variability in outcomes that arises even when decisions are well-informed and rational.

Example:

- Two identical analysts make the same recommendation based on the same data. One succeeds due to a favorable market reaction, the other fails because of random factors outside their control.

Why it matters:

Noise explains why good decisions sometimes fail and why markets feel unfair in the short term. Recognizing noise helps investors separate process quality from luck-driven results.

4. Luck vs Skill (Michael Mauboussin, 2007–2012)

Definition: Understanding which outcomes are due to skill and which are due to luck.

Example:

- A trader who makes 10 consecutive winning trades might appear highly skilled, but in a noisy market, some wins could be pure chance.

Why it matters:

Separating luck from skill allows investors to evaluate their strategies accurately, avoid overconfidence, and focus on processes that survive randomness over time.

5. Fat Tails (Nassim Taleb, 2007)

Definition: In probability distributions, “fat tails” mean extreme outcomes (very big wins or losses) occur more frequently than standard models predict.

Example:

- The 1987 stock market crash or the 2008 housing collapse were extreme events that traditional models underestimated.

Why it matters:

Markets are riskier than simple averages suggest. Fat tails show why rare but devastating losses can wipe out seemingly rational decisions. Understanding this keeps investors cautious and prepared.

6. Financial Instability Hypothesis (Hyman Minsky, 1986)

Definition: Financial systems naturally swing between stability and fragility. Prolonged calm encourages risk-taking, which eventually leads to crises.

Example:

- In the 2000s, years of stable housing prices encouraged excessive leverage, culminating in the 2008 crash.

Why it matters:

Minsky shows why even rational, risk-aware investors can be caught in systemic events. It emphasizes that market outcomes are shaped by collective behavior, leverage, and structural fragility—not individual mistakes alone.

Connecting the Dots: Why Experts Focus on Process, Not Results

Different thinkers, different disciplines, same lesson:

Complex systems punish outcome-based thinking.

- Outcome bias tricks investors into overreacting to results.

- Hindsight bias creates false confidence in predicting crises.

- Noise and luck make short-term results unreliable.

- Fat tails and systemic instability amplify risks that are invisible in quiet markets.

The takeaway is simple but profound:

- The quality of your decisions matters more than the immediate results.

- Success in investing is about surviving uncertainty and compounding good processes over time.

Practical Tools You Can Actually Use

1. Decision Journaling

Before investing, write:

- Why you’re investing

- What could go wrong

- Expected value

- Range of outcomes

- Time horizon

This becomes your benchmark—not the outcome.

2. Pre-Mortems

Ask:

“If this fails badly, why?”

Especially useful for “can’t miss” ideas.

3. Position Sizing

Good ideas can be early or wrong.

Size positions so mistakes are survivable.

4. Time-Horizon Discipline

Don’t judge long-term strategies on short-term results.

5. Learning Without Self-Blame

Use outcomes to:

- Improve probability estimates

- Understand risks better

- Not to attack your past self.

Nuance: This Is Not an Excuse for Stubbornness

Separating process from outcome does not mean:

- Ignoring new information

- Refusing to change your mind

It means:

- Update beliefs when facts change (Bayesian updating)

- Do not update beliefs just because of pain

The difference is new information, not emotional discomfort.

The Core Takeaway

Markets reward:

- Survival

- Discipline

- Time

They do not reward:

- Being right quickly

- Feeling smart

- Winning every year

The goal of investing is not to always be right,

but to survive long enough for good decisions to compound.

Reflective Prompt

Think of a past investment you regret.

Ask:

- Was the decision flawed at the time?

- Or was the outcome unlucky?

Learning the difference is the beginning of investing maturity.

About Swati Sharma

Lead Editor at MyEyze, Economist & Finance Research WriterSwati Sharma is an economist with a Bachelor’s degree in Economics (Honours), CIPD Level 5 certification, and an MBA, and over 18 years of experience across management consulting, investment, and technology organizations. She specializes in research-driven financial education, focusing on economics, markets, and investor behavior, with a passion for making complex financial concepts clear, accurate, and accessible to a broad audience.

Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes only and should not be interpreted as financial advice. Readers should consult a qualified financial professional before making investment decisions. Assistance from AI-powered generative tools was taken to format and improve language flow. While we strive for accuracy, this content may contain errors or omissions and should be independently verified.