Tutorial Categories

Last Updated: January 13, 2026 at 19:30

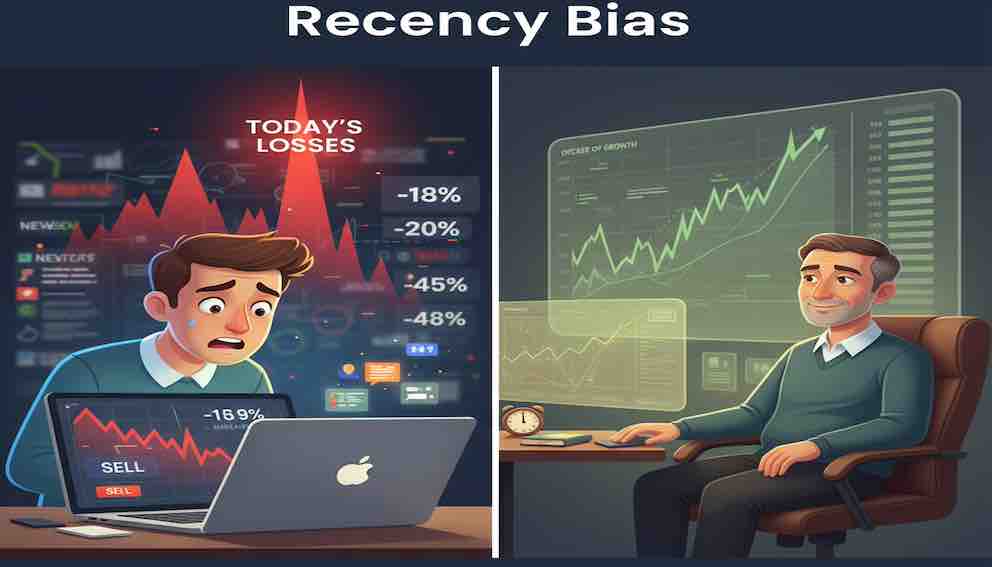

Recency Bias: Why the Latest News Feels So Important - Behavioral Finance Series

Why does the latest market news feel so urgent? Recency bias makes recent events loom larger than older, equally important information. From panic-selling during short-term dips to overreacting to headlines, this subtle cognitive bias can quietly sabotage investors’ decisions. Learn how experts counter it with rules, reflection, and historical context—and discover strategies to keep your long-term plan on track.

Imagine this: You read a news headline that “Tech stocks are crashing today.” Immediately, you feel panic creeping in. You check your portfolio and contemplate selling a tech ETF—even though your long-term investment plan is sound. A week later, the market rebounds, but the uneasy feeling lingers. Why does the most recent event feel so disproportionately important, even when it’s statistically minor? Welcome to recency bias, a subtle but powerful behavioral trap that affects investors, traders, and decision-makers alike.

Core Theory: Understanding Recency Bias

Recency bias is a cognitive bias where people overweight recent information and underweight older, equally relevant data. It is a type of availability heuristic—a mental shortcut where we rely on easily recalled events rather than the full picture.

Psychologically, recency bias is linked to:

- Emotional salience: Recent events feel more “real” or urgent.

- Memory accessibility: New information is easier to recall than older data.

- System 1 dominance: Fast, intuitive thinking favors what is vivid and immediate over what is abstract or historical.

Example:

A novice investor sees a sudden 10% drop in a stock over two days. They panic-sell because the immediate loss feels significant, ignoring that the stock historically fluctuates ±15% every month. Their judgment is dominated by recent events rather than long-term data.

Financial Consequences: How Recency Bias Plays Out

Recency bias can impact financial decisions in multiple ways:

- Overreacting to short-term market news

- Investors might buy high during a rally or sell low during a dip, chasing short-term trends rather than sticking to a disciplined plan.

- Mispricing risk

- When the latest downturn dominates perception, investors may exaggerate risk exposure, moving into cash or ultra-safe assets unnecessarily.

- Portfolio churn and excessive trading

- Reactionary trading increases costs (commissions, taxes) and erodes long-term returns.

- Ignoring historical context

- Focusing solely on the past week’s or month’s performance makes investors blind to broader trends, mean reversion, and base rates.

Example:

During the 2008 financial crisis, many retail investors sold equities after watching daily headlines about bank failures. In contrast, long-term investors who held onto diversified portfolios recovered much of their losses in the subsequent decade.

Expert vs Novice Behavior

Novices often succumb to recency bias because:

- They overweight daily news or social media updates.

- They lack context on historical volatility or market cycles.

- Emotions are intertwined with new information, triggering impulsive action.

Experts, while not immune, build processes and “nudges” to counteract recency bias:

- Using historical data and statistical context: Professionals analyze multi-year trends rather than daily headlines.

- Setting rules-based plans: Portfolio rebalancing schedules and target allocations are followed irrespective of short-term news.

- Structured reflection: Analysts maintain decision journals to separate gut reactions from objective evaluation.

- Team perspectives: Investment committees discuss new information collectively, reducing the influence of one individual’s emotional response.

- Affect heuristic awareness: Professionals acknowledge that emotionally charged recent events can color judgment, and they intentionally slow decision-making in response.

Example:

A fund manager doesn’t sell a tech stock after one volatile week. They evaluate quarterly performance, macroeconomic factors, and historical patterns, making changes only if the underlying thesis changes—rather than reacting to a single headline.

Practical Strategies to Mitigate Recency Bias

Pre-commitment to a plan : Define asset allocation and risk limits in advance. Decisions are then anchored in a systematic plan rather than moment-to-moment news.

Set evaluation horizons : Review performance quarterly or annually rather than daily. Reduces the emotional weight of short-term fluctuations.

Quantitative context : Use historical returns, volatility metrics, and probability analysis. Comparing recent data with long-term averages helps calibrate reactions.

Decision journaling : Record why a trade or change is made. After a month or quarter, evaluate whether recent news drove behavior unnecessarily.

Automation : Automated contributions, rebalancing, or stop-loss mechanisms can prevent reactive moves prompted by the latest headlines.

Example:

Instead of checking daily stock prices, a young investor sets up automatic monthly investments in a diversified index fund. They also maintain a journal, noting that a recent tech drop tempted them to sell—but they held their position and avoided emotional losses.

Nuance & Debate

Recency bias is not always irrational. Its effect depends on the situation and how recent information is used.

When Recency Can Be Useful

From an evolutionary point of view, paying more attention to recent events can make sense when the environment is changing. If the rules of the game are shifting—such as during major regulatory changes or technological breakthroughs—new information may genuinely matter more than old data.

The real challenge for investors is telling the difference between a true structural change and short-term market noise.

Not the Same as “The Trend Is Your Friend”

In strategies like momentum investing or technical analysis, reacting to recent price movements is intentional and disciplined. Recency bias becomes a problem when investors apply this logic inconsistently—reacting emotionally to short-term moves or assuming a brief trend will last forever without evidence.

Historical Lessons

- 2008 Financial Crisis: Many retail investors sold in panic after seeing alarming daily headlines, even though diversified portfolios were fundamentally sound and eventually recovered.

- Dot-com Bubble (late 1990s): Investors projected recent, rapid tech stock gains far into the future, ignoring long-term valuation norms. Recency bias combined with representativeness bias created the illusion that a short-term boom reflected a permanent new economic era.

What Reduces Recency Bias

- Cultural and professional settings matter. Some environments reward quick reactions, while others emphasize careful, structured decision-making.

- Experience, comfort with data, and familiarity with market history all reduce the tendency to overreact to recent events.

Advanced Note

Professional institutions use tools like decision reviews (post-mortems), experience tracking, and probability-based updates to limit recency bias. By regularly comparing recent outcomes with long-term data, teams develop more balanced and less emotionally driven judgment.

Reflective Prompt

Think about your own financial decisions:

- Have you ever made a trade or investment choice primarily because of a recent news event?

- How might you structure your process to reduce the emotional impact of recency bias?

- When could weighting recent information actually be rational?

Clear Takeaway

Recency bias tricks us into thinking the present moment is disproportionately important. By slowing down, using historical context, automating decisions, and reflecting systematically, investors can separate signal from noise. Long-term wealth isn’t built by reacting to the latest headline—it’s built by disciplined, evidence-based decision-making.

About Swati Sharma

Lead Editor at MyEyze, Economist & Finance Research WriterSwati Sharma is an economist with a Bachelor’s degree in Economics (Honours), CIPD Level 5 certification, and an MBA, and over 18 years of experience across management consulting, investment, and technology organizations. She specializes in research-driven financial education, focusing on economics, markets, and investor behavior, with a passion for making complex financial concepts clear, accurate, and accessible to a broad audience.

Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes only and should not be interpreted as financial advice. Readers should consult a qualified financial professional before making investment decisions. Assistance from AI-powered generative tools was taken to format and improve language flow. While we strive for accuracy, this content may contain errors or omissions and should be independently verified.