Last Updated: February 7, 2026 at 19:30

The Anatomy of a Bond: Understanding Cash Flows, Coupons, and Maturity

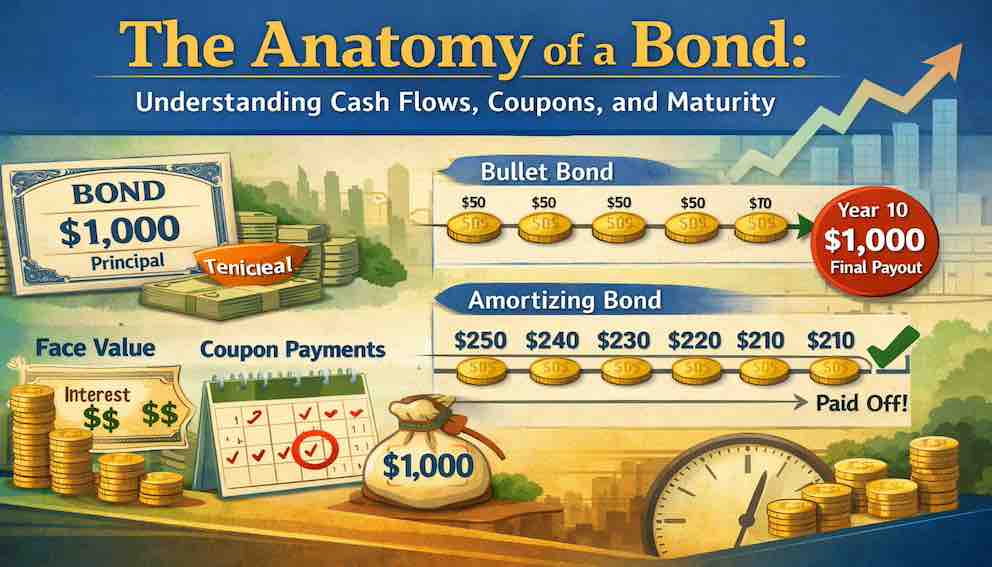

A bond is, at its core, a loan written down as a contract. One side borrows money, agrees to pay interest regularly, and promises to repay the original amount on a specific date. In this tutorial, we break that contract into its main parts: Face Value (the amount loaned), Coupon (the interest you earn), and Maturity (when and how the loan ends). You’ll learn how to read any bond’s terms, sketch its payment timetable, and see the difference between a lump‑sum repayment and a gradual paydown. Once you understand this “anatomy,” you can start assessing risk, planning your income, and thinking about how bonds are priced and how their cash flows fit your goals.

Introduction: Reading the Bond Blueprint

In the previous tutorial, we treated a bond as a formal promise—a rule‑based contract between the issuer and the investor. Now it’s time to read the fine print of that promise. When you look at a bond, you are not just seeing a price or a yield; you are looking at a blueprint for future cash flows.

That blueprint has three non‑negotiable specifications:

- Face Value – How much is being borrowed.

- Coupon – What interest is paid on that loan.

- Maturity & Structure – When and how the loan ends, either as a single lump sum (a bullet bond) or in installments (an amortizing bond).

Understanding this anatomy is like studying a map before a journey: it shows your starting point (how much you lend), the stops along the way (interest payments), and your final destination (principal repayment). Once you grasp these elements, a bond stops being a vague promise and becomes a predictable schedule of cash flows you can analyze, plan around, and eventually price.

The Bond Market in Context

The bond market is huge—actually larger than the stock market at the global level. Estimates(in 2025) put the global fixed‑income market around 140–145 trillion dollars, versus roughly 130 trillion for global equities, and in the U.S. outstanding bonds slightly exceed the size of the U.S. stock market.

Bonds are first sold in the primary market, where governments auction new issues and companies raise money through investment banks that place bonds with big investors such as pension funds, insurers, and mutual funds. After that, bonds trade between investors in the secondary market, mostly over‑the‑counter via dealers and electronic platforms, and sometimes on exchanges that retail investors can access through brokers.

In the U.S., ownership is spread across the financial system. Large holders of Treasury and other bonds include the Federal Reserve, foreign investors, banks, insurance companies, pension funds, mutual funds and ETFs, and, to a smaller but growing extent, households.

Part 1: Face Value – The Principal of the Matter

The face value (also called par value or principal) is the amount the issuer borrows and promises to repay at maturity. Think of it as the anchor of the bond: it stays the same in the contract even if the bond’s market price later goes up or down.

Example: The Neptune City Water Bond

Neptune City issues a bond to rebuild its water treatment plant:

- Bond face value: $1,000

- Your action: You lend Neptune City $1,000 by buying one bond

- Issuer’s promise: In 10 years, they will repay the $1,000 principal

This $1,000 does three jobs:

- It sets the base for interest calculations (coupon payments are a percentage of this amount).

- It defines what you are ultimately owed at maturity.

- It acts as the reference point when investors talk about the bond trading “at par,” “below par,” or “above par.”

Even if the bond later trades for $950 or $1,050 in the market, the contract still says: “At maturity, we will pay the holder $1,000.”

Part 2: The Coupon – Your Interest Paycheck

Lending money is not free. The coupon is the interest the issuer pays you for the use of your money. It has two key pieces:

- The coupon rate: the annual interest rate, expressed as a percentage of face value.

- The coupon payment: the actual cash amount you receive each period.

Back to the Neptune City bond:

- Face value: $1,000

- Coupon rate: 5% per year

- Annual interest: 5% of $1,000 = $50

In many markets (including the U.S.), bonds pay interest semiannually. That means you receive $25 every six months, like clockwork, for ten years.

This regularity is the essence of fixed income: you know when money is coming in, and (barring default) you know how much.

Floating‑Rate Bonds

Not all coupons are fixed. Some bonds have floating or variable‑rate coupons, which reset based on a reference rate plus a fixed margin. A common reference rate is SOFR (the Secured Overnight Financing Rate), which is an interest rate that reflects the cost of very short‑term borrowing between large financial institutions. If a bond’s coupon is “SOFR + 2%,” it means the interest you earn will move up and down with SOFR, with an extra 2% added on top.

Example floating‑rate structure:

- Coupon formula: SOFR + 2%

- Year 1: SOFR is 3% → coupon = 5% → payment = $50

- Year 2: SOFR rises to 4% → coupon = 6% → payment = $60

- Year 3: SOFR falls to 2% → coupon = 4% → payment = $40

The timing of payments is still predictable (every period), but the amount can go up or down. That creates both opportunity (higher income if rates rise) and risk (lower income if rates fall).

Part 3: Maturity & Redemption – The End of the Loan

The maturity of a bond is its end date: the day the issuer must repay the face value and the contract ends. That repayment is called redemption. How the principal is repaid—at once or gradually—defines the bond’s structure and affects both risk and cash flow.

Structure A: Bullet Bonds – The Lump Sum

A bullet bond pays only interest during its life and returns the full principal at maturity.

Example: 10‑year, $1,000 bullet bond with 5% annual coupon

- Years 1–9: $50 interest each year

- Year 10: $50 interest + $1,000 principal

Your cash flows are light but steady for most of the term, with one large payment at the end. This is simple to understand but keeps your entire principal exposed to the issuer’s credit risk for the full 10 years. Bullet bonds also tend to be more sensitive to interest rate changes because all the principal is returned at the very end.

Structure B: Amortizing Bonds – The Installment Plan

An amortizing bond returns principal in chunks over time, alongside interest. Each year (or period) you get part of your principal back, so your exposure shrinks.

Example: 5‑year, $1,000 bond at 5% coupon, with equal principal repayments

Year 1:

- $200 principal + $50 interest (5% of $1,000) = $250

Year 2:

- $200 principal + $40 interest (5% of $800) = $240

Year 3:

- $200 principal + $30 interest (5% of $600) = $230

Year 4:

- $200 principal + $20 interest (5% of $400) = $220

Year 5:

- $200 principal + $10 interest (5% of $200) = $210

Here:

- Payments are larger at the start and shrink over time.

- With each principal repayment, your credit risk falls because less of your money is still at stake.

By contrast, with a bullet bond all your principal sits on the line until the maturity date.

Credit Risk and Priority

Both structures carry credit risk—the risk the issuer does not pay on time or in full. In a default or bankruptcy, bondholders have priority over shareholders in the repayment queue, which improves their chances of recovery. However:

- Bullet bonds keep the full principal at risk for longer.

- Amortizing bonds gradually reduce that risk as principal flows back to you.

Understanding this timing of risk is a key part of evaluating any bond.

Part 4: The Cash Flow Calendar – Your Complete Picture

Once you know the face value, coupon, and structure, you can draw a cash flow calendar for your bond.

Bullet bond timeline:

- Regular interest payments (e.g., every six months).

- A large spike at maturity: final interest + full principal.

Amortizing bond timeline:

- Larger early payments that mix principal and interest.

- Payments that step down over time as the remaining principal shrinks.

Thinking in timelines turns the legal contract into a practical income plan. You can mark expected cash inflows on a calendar, see when you will have money to reinvest, and check whether the timing matches your future needs (tuition, a home purchase, retirement, etc.).

Part 5: Why This Anatomy Is Your Superpower

Knowing the internal structure of a bond gives you three powerful abilities.

1. You Can See What the Market Is Pricing

A bond’s price in the market is just the present value of all its future cash flows discounted at the market’s required return. Once you know the schedule of coupons and principal repayments, you know exactly what is being valued.

Example: Neptune City bond

- Promises $50 every year for 10 years and $1,000 at the end.

- If new bonds of similar risk pay only 3%, your 5% coupons look generous, so the market price will sit above $1,000.

- If new bonds pay 7%, your 5% coupons look stingy, so the market price will fall below $1,000.

The contract (face value and coupon) hasn’t changed; only the price that investors are willing to pay for that stream of cash flows has moved.

2. You Can Assess Risk Quickly

Longer bullet bonds:

- More sensitive to interest‑rate moves (because principal is all at the end).

- Principal is exposed to credit risk for more time.

Amortizing bonds:

- Principal risk falls over time as you get money back.

- Total interest you receive usually declines because it is calculated on a shrinking balance.

Floating‑rate bonds:

- Help if rates rise (income can increase).

- Hurt your income if rates fall (payments can drop).

The combination of maturity, structure, and coupon type tells you a lot about how “fragile” or “robust” a given bond is.

3. You Can Match Bonds to Real‑World Goals

Once you see a bond as a schedule of cash flows, you can match it to specific needs:

- Need a lump sum in 5 years? A 5‑year bullet bond aligns principal repayment with your goal.

- Need steady income every six months? Choose bonds with regular coupon payments and staggering maturities.

- Want to reduce risk over time? Consider amortizing structures where principal comes back gradually.

4. You See the Trade‑Offs Clearly

- Fixed coupons are predictable, but inflation can chip away at what those payments can buy.

- Bullet structures give a clean lump sum at the end but keep all your principal exposed longer.

- Amortizing structures reduce credit risk over time but front‑load your cash flows and reduce interest paid later.

Conclusion: From Blueprint to Predictable Cash Flows

You have now broken the bond contract into three vital components:

- Face Value: The principal you lend and are promised back.

- Coupon: The interest you earn on that principal.

- Maturity & Structure: When and how the principal is repaid—either as a lump sum (bullet) or in installments (amortizing).

Thinking of a bond as a dated list of cash flows lets you answer two critical questions immediately: How much will I get? and When will I get it? From there, it becomes much easier to think about interest‑rate risk, credit risk, and the variability of payments in floating‑rate bonds.

This mental model prepares you for the next step: how markets turn these cash‑flow calendars into prices, why bond prices move in the opposite direction to interest rates, and how yields tie it all together.

About Swati Sharma

Lead Editor at MyEyze, Economist & Finance Research WriterSwati Sharma is an economist with a Bachelor’s degree in Economics (Honours), CIPD Level 5 certification, and an MBA, and over 18 years of experience across management consulting, investment, and technology organizations. She specializes in research-driven financial education, focusing on economics, markets, and investor behavior, with a passion for making complex financial concepts clear, accurate, and accessible to a broad audience.

Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes only and should not be interpreted as financial advice. Readers should consult a qualified financial professional before making investment decisions. Assistance from AI-powered generative tools was taken to format and improve language flow. While we strive for accuracy, this content may contain errors or omissions and should be independently verified.