Last Updated: February 10, 2026 at 18:30

Credit Ratings Explained: What They Measure, What They Miss, and Why Markets Usually Move First

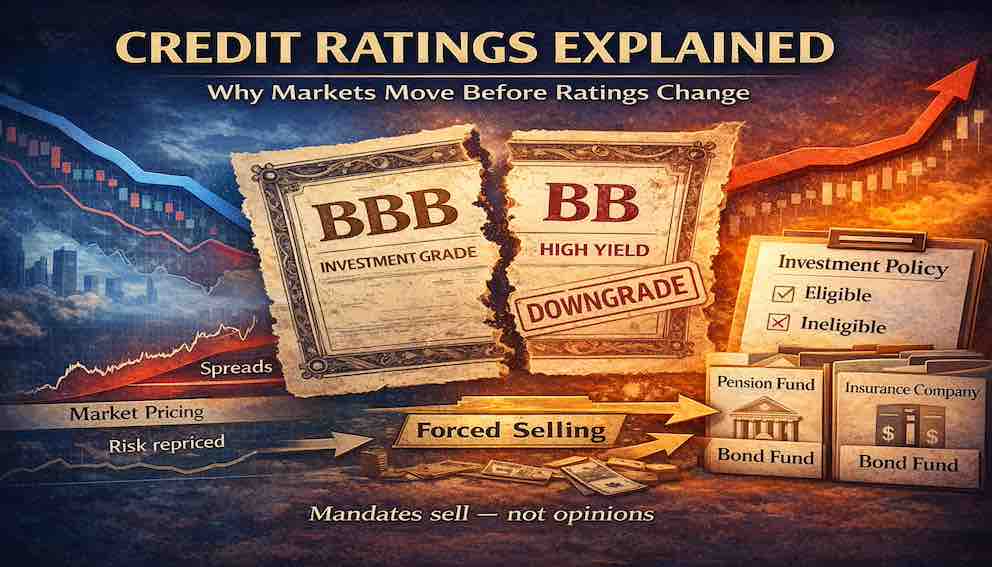

Credit ratings are often treated as authoritative safety judgments, yet they are best understood as structured summaries of risk rather than tools for discovering it. This tutorial explains what ratings capture, what they intentionally leave out, and why bond prices often move months before a rating changes. We explore how a single downgrade—especially from investment grade to high yield—can trigger forced selling, sharp price declines, and lasting stigma, creating so-called “fallen angels.” In contrast, improving “rising stars” tend to receive quiet market recognition long before an upgrade arrives. By the end, readers learn how to use credit ratings as a helpful starting point without outsourcing independent judgment.

Introduction: Why Credit Ratings Still Matter, Even When They Lag

In our previous tutorial, we saw credit spreads act as the market’s real-time pulse of doubt. Imagine two technology companies: StableTech Inc. and GrowthCast Ltd. Both carry a ‘BBB’ credit rating, placing them at the lower end of investment grade. Yet StableTech’s bonds trade at a spread of 1.8% over Treasuries, while GrowthCast’s bonds trade at 2.5%. That 0.7% difference is not random. It is the market quietly expressing concern about GrowthCast’s aggressive expansion strategy, rising costs, and thinner margin for error, even though the formal rating labels remain identical.

This example highlights an uncomfortable truth for many investors: the market often begins to reassess risk well before rating agencies make any official change. Prices move first, yields adjust, and spreads widen or tighten as investors continuously update their expectations.

Yet despite this, we still live in a world deeply shaped by credit ratings. Your retirement plan’s bond fund likely contains language such as “no holdings below investment grade.” Insurance companies, pension funds, and endowments operate under similar constraints. These letter grades—‘AAA,’ ‘BBB,’ ‘BB,’ and so on—act as powerful gatekeepers that determine who can own what.

This tutorial aims to demystify that power. We explore what ratings are designed to do, why they change slowly, and how investors can use them intelligently without being misled by their apparent authority.

What Credit Ratings Are Designed to Measure (and What They Aren’t)

At their core, credit ratings are opinions about default risk. They answer a narrowly defined question: How likely is this borrower to fail to meet its contractual debt obligations in full and on time, under normal economic conditions and plausible stress scenarios?

To arrive at this opinion, rating agencies such as Moody’s, S&P, and Fitch behave like extremely cautious loan officers. They examine financial statements to assess leverage, interest coverage, and cash-flow stability. They study the issuer’s business profile, including competitive position, industry cyclicality, and exposure to regulatory or technological disruption. They evaluate management behavior, governance practices, and historical decision-making, particularly during past periods of stress.

However, it is just as important to understand what credit ratings are not attempting to measure. A rating is not an assessment of whether a bond is attractively priced. It does not predict where the bond’s price will trade next month. It does not attempt to capture day-to-day volatility or shifts in market sentiment.

This deliberate narrowness is not a flaw; it is a design choice. Ratings are built to be stable reference points for institutions that need consistency, comparability, and regulatory clarity. For an individual investor, however, this stability has a cost. It means that ratings function more like a rearview mirror than a crystal ball.

Why the Market (and Price) Moves First: The Information Gap

Markets and rating agencies process information on fundamentally different timelines. Markets update continuously. Every earnings release, management call, macroeconomic data point, and competitive development nudges investor expectations slightly higher or lower. Prices adjust accordingly, often in small increments that accumulate over time.

Rating agencies, by contrast, move deliberately. Their process involves formal reviews, committee discussions, and a high burden of proof before any change is made. This caution exists to avoid frequent reversals that would undermine the usefulness of ratings as stable benchmarks.

Returning to GrowthCast Ltd. helps illustrate this gap:

- Month 1: GrowthCast reports negative free cash flow for the first time. Informed investors sell. The bond price slips, and the spread widens.

- Month 3: A key product launch disappoints. Analysts grow more cautious. The spread widens further, and the bond is now down 8%.

- Month 5: After a formal review, S&P downgrades GrowthCast from ‘BBB’ to ‘BB+.’ Headlines announce the downgrade, but the economic reality has been unfolding for months.

The rating change does not reveal new information. It confirms what the market has already been pricing.

This distinction reflects a deeper design philosophy. Credit ratings are built to answer the question, “Is this borrower still broadly consistent with its category?” Markets are answering a different question entirely: “How has the probability distribution of outcomes changed today?” The lag between the two is not an accident. It is the cost of stability.

Capital Structure Matters More Than the Letter Grade

An additional nuance often overlooked is that ratings summarize issuer-level creditworthiness, but bonds exist within a capital structure. Two bonds issued by the same company can share a rating yet carry meaningfully different risks depending on their seniority.

A senior secured bond may be protected by collateral and sit at the top of the repayment hierarchy, while a subordinated bond absorbs losses much earlier in a stress scenario. Until distress becomes obvious, both may carry similar ratings. When conditions deteriorate, however, recovery outcomes can diverge dramatically.

This is another reason ratings should be treated as summaries rather than complete risk descriptions. They compress complexity for comparability, but investors must still understand where their bond sits in the line of claims.

The Domino Effect: How a Downgrade Can Crush a Price

A downgrade does more than adjust a label; it can trigger a mechanical chain reaction. This is most severe when a bond crosses the boundary from investment grade (‘BBB-’) into high yield (‘BB+’).

Consider a local teachers’ pension fund whose charter states: “At least 80% of the portfolio must be invested in investment-grade bonds.” The fund holds $10 million of GrowthCast bonds.

Before the downgrade, those bonds count toward the 80% requirement. After the downgrade, they do not. Compliance systems flag the holding immediately. The portfolio manager may believe GrowthCast will survive, but belief is irrelevant. The mandate requires selling.

Now imagine hundreds of funds with similar rules receiving the same alert at the same time. The resulting selling pressure has little to do with default probability and everything to do with regulatory mechanics. Prices fall sharply, not because the business suddenly collapsed, but because ownership constraints changed overnight.

This is why fallen angels often experience violent price declines that feel disproportionate to the underlying fundamentals.

Fallen Angels and Credit Cycles

Downgrades do not occur evenly over time. They cluster late in credit cycles, when earnings are already under pressure, refinancing conditions are tightening, and investor tolerance for risk is shrinking. By the time rating agencies act, spreads have often been warning of stress across entire sectors.

In this context, a fallen angel downgrade is frequently a liquidity event rather than a solvency event. The market structure amplifies the move, even if the company remains operationally viable.

Understanding this cycle timing helps investors avoid conflating price pain with imminent default.

The Asymmetric Journey: Fallen Angels vs Rising Stars

The market treats deteriorating and improving credits very differently.

A fallen angel downgrade is sudden and violent, driven by forced selling and a rapid change in investor base. It resembles a trap door opening beneath the bond.

A rising star upgrade, by contrast, is gradual and quiet. Consider AutoParts Co., which steadily pays down debt over several years. As leverage declines and cash flows improve, spreads tighten long before any formal upgrade. When the upgrade finally arrives, most of the price appreciation has already occurred. There is no forced buying frenzy, because investment-grade funds can buy at their discretion.

This asymmetry reinforces the central lesson: ratings confirm trends; they rarely initiate them.

Conclusion and Practical Application: Using Ratings as a Tool, Not a Crutch

So how should a thoughtful investor use credit ratings?

Start with the rating, but do not stop there. A ‘BBB’ rating tells you that the issuer is considered minimally investment grade, not that it is safe in all circumstances. Look at where the bond trades relative to peers. Persistent spread widening is often the market’s early warning system.

Respect the cliff at the investment-grade boundary. A bond rated ‘BBB-’ carries asymmetric downside risk because the consequences of a downgrade are mechanically severe.

Finally, perform a simple snapshot analysis. Observe whether leverage is rising or falling and whether earnings comfortably cover interest payments. You are not forecasting default; you are watching direction and momentum. These trends often preview rating actions long before they occur.

What We Have Learned

Credit ratings are powerful, slow-moving summaries of credit risk. They provide essential standardization for the financial system, but they are not designed to discover emerging problems or identify tactical opportunities. Markets express doubt through prices and spreads long before ratings change. Downgrades—especially to high yield—often reflect liquidity mechanics and mandate constraints as much as economic reality.

By learning to interpret ratings in context, alongside spreads, capital structure, financial trends, and the credit cycle, investors transform ratings from rigid labels into useful inputs. This shift—from passive label-reading to active interpretation—is at the heart of sound fixed-income thinking.

About Swati Sharma

Lead Editor at MyEyze, Economist & Finance Research WriterSwati Sharma is an economist with a Bachelor’s degree in Economics (Honours), CIPD Level 5 certification, and an MBA, and over 18 years of experience across management consulting, investment, and technology organizations. She specializes in research-driven financial education, focusing on economics, markets, and investor behavior, with a passion for making complex financial concepts clear, accurate, and accessible to a broad audience.

Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes only and should not be interpreted as financial advice. Readers should consult a qualified financial professional before making investment decisions. Assistance from AI-powered generative tools was taken to format and improve language flow. While we strive for accuracy, this content may contain errors or omissions and should be independently verified.