Last Updated: February 2, 2026 at 10:30

The Investor's Greatest Enemy: How Your Own Psychology Quietly Erodes Returns - Investing Wisdom series

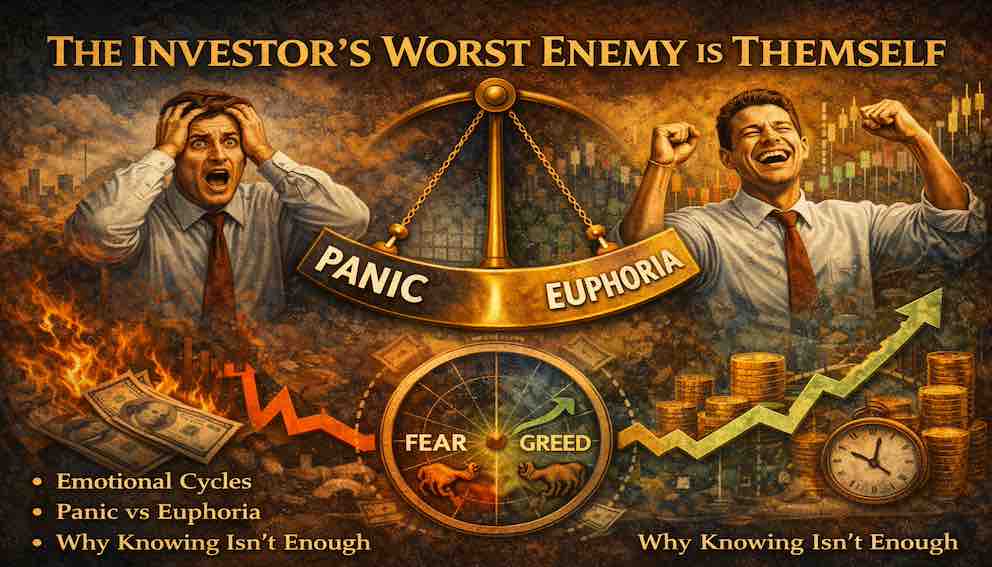

Most investors don’t fail because they choose the wrong stocks—they fail because they react emotionally at the wrong time. This tutorial explains how emotional cycles work, why panic and euphoria override logic, and why simply “knowing better” is not enough. Understanding your own psychology is the foundation of long-term investing success.

The Uncomfortable Truth We Try to Avoid

Consider for a moment the last time you made a poor financial decision. Perhaps you sold an investment during a market decline, only to watch it recover. Maybe you bought into a "hot" trend at its peak. In the aftermath, what explanation did you offer yourself?

Most likely, you blamed external forces. "The market was irrational." "The news was misleading." "No one could have predicted this." These explanations provide psychological comfort—they place the cause outside ourselves, preserving our self-image as rational beings.

But when researchers examine the aggregate behavior of millions of investors across decades, a different pattern emerges. Study after study reveals that individual investors consistently underperform the very markets in which they invest. This isn't because they choose poor investments, but because their timing is consistently counterproductive. They tend to buy after prices have risen significantly and sell after they have fallen substantially. The problem isn't the market. The problem is us.

This realization might seem discouraging at first glance, but it contains a liberating truth. If the primary obstacle to investment success resides within our own psychology, then it becomes something we can understand, anticipate, and manage. We cannot control markets, but we can learn to recognize and navigate our own predictable patterns of thought and emotion.

The Evolutionary Mismatch: Why Investing Feels Unnatural

To understand why we struggle, we must appreciate what our brains were designed to do. For the vast majority of human existence, survival depended on rapid responses to immediate threats and opportunities. Our ancestors who hesitated when faced with danger—who carefully analyzed whether the rustling bush contained a predator or just the wind—did not pass on their genes. Those who acted quickly, who avoided losses instinctively, and who followed the safety of the group survived.

These evolutionary adaptations served us well for millennia, but they create significant challenges in the modern financial environment. Consider three core tendencies:

First, our brains are exquisitely sensitive to loss. Research in behavioral economics demonstrates that the psychological pain of losing a sum of money is roughly twice as intense as the pleasure of gaining the same amount. This "loss aversion" makes perfect evolutionary sense—losing your food stores could mean starvation, while gaining extra might merely mean comfort. But in investing, this wiring causes us to perceive temporary market declines as existential threats, triggering panic responses disproportionate to the actual risk.

Second, we are social creatures who find safety in numbers. When everyone else is fleeing, our instincts scream that we should flee too. When others are rushing toward an opportunity, our instincts suggest safety lies in joining them. This herd mentality served early humans well—if the tribe was moving, staying behind was dangerous. In financial markets, however, this instinct leads to buying at peaks (when everyone is excited) and selling at troughs (when everyone is fearful).

Third, our brains crave patterns and stories. We are uncomfortable with randomness and uncertainty. So when prices move, we instinctively look for narratives to explain them. A market decline becomes a "crisis" with villains and causes. A rally becomes a "revolution" led by visionary leaders. These stories feel satisfying, but they often mislead us into believing we understand what is fundamentally unpredictable.

The crucial insight is this: Successful investing often requires doing what feels wrong. It requires staying calm when your instincts scream danger. It requires skepticism when everyone else seems certain. It requires patience when your brain demands action.

The Emotional Pendulum: A Predictable Cycle

Market prices fluctuate, but investor emotions swing in a remarkably consistent rhythm. Understanding this rhythm is the first step in stepping outside of it.

Imagine the early stages of a market recovery. Prices have been depressed, but they begin a slow, tentative climb. News remains mixed, but improving. At this stage, investing requires a quiet confidence. There's little social proof—most people are still wary. The investors who participate here are often those who have prepared themselves psychologically for this moment. They are not reacting to excitement, but following a predetermined plan.

As the recovery gains momentum, a new phase begins. Positive returns become visible in statements. Friends and colleagues begin discussing their gains. Financial media shifts its tone from caution to optimism. This is where emotions start to influence decisions. People who missed the early stages begin buying, not because of careful analysis, but because of a growing fear of being left behind. The narrative shifts from "this might be a good opportunity" to "everyone is making money."

Then comes the phase of euphoria. Prices have risen for an extended period. Negative news is dismissed as irrelevant. Stories circulate about ordinary people achieving extraordinary gains. Risk feels like an abstract concept because nothing has gone wrong recently. At this point, buying feels not just reasonable, but obligatory. Not investing feels like missing out on a fundamental truth everyone else has grasped. This is when people who have never shown interest in markets suddenly become enthusiastic investors. The collective emotion overrides individual caution.

The turning point often arrives quietly. A modest decline begins. Initially, it's explained away as a "healthy correction" or "profit-taking." But as the decline continues, confidence erodes. The narratives that seemed so convincing days earlier begin to unravel. The first emotional response is usually anxiety, which then deepens into fear.

Fear is a powerful state. It narrows our focus to immediate threats. In this state, the long-term perspective that seemed so clear during calm moments disappears. All that matters is stopping the pain now. Selling, even at a loss, provides emotional relief. It feels like regaining control. This is the precise moment when investors often convert temporary paper losses into permanent ones.

After the selling subsides, a period of disillusionment often follows. The investor, having locked in losses, swears off markets entirely. They may declare the system broken or themselves incompetent. They withdraw, often just as the cycle begins its slow turn upward again.

This pendulum doesn't swing because markets are cruel. It swings because human psychology is predictable. The same emotions, triggered by the same price movements, produce the same behaviors across generations of investors who think their situation is unique.

The Illusion of Control: Why Knowledge Isn't Enough

A common misconception is that education alone can solve these psychological challenges. We imagine that if we just learn enough about financial statements, economic indicators, or portfolio theory, we will become immune to emotional decision-making. The evidence suggests otherwise.

Consider the case of Isaac Newton, one of the most brilliant minds in human history. After making a substantial profit during the early stages of the South Sea Bubble in 1720, Newton reinvested near the peak and lost £20,000—a fortune at the time. His famous lament captures the problem perfectly: "I can calculate the motion of heavenly bodies, but not the madness of people."

Newton didn't lack intelligence or information. He lacked emotional detachment. His knowledge of mathematics couldn't protect him from the psychological pull of a speculative frenzy.

Modern examples abound. During the dot-com bubble of the late 1990s, countless financially literate professionals—doctors, lawyers, engineers—poured money into technology companies with no earnings and questionable business models. They understood valuation principles. They could read financial statements. Yet they invested anyway, driven by the powerful emotions of excitement and fear of missing out.

The problem is neurological. When we experience strong emotions like fear or excitement, activity shifts from the prefrontal cortex—the part of the brain responsible for rational analysis and long-term planning—to more primitive regions associated with immediate survival. In these states, we don't think; we react. The knowledge we've carefully accumulated becomes inaccessible, overridden by more urgent signals.

This explains why you can read about market history on a quiet Saturday afternoon and feel completely prepared for volatility, yet find yourself paralyzed with anxiety when your portfolio actually declines on a Tuesday morning. The intellectual understanding exists in one neurological context; the decision happens in another.

Engineering Discipline: From Willpower to Structure

We can't always control our emotions with willpower or knowledge alone. So what's the solution? We need to build external systems that guide us toward rational decisions when our own judgment is clouded.

Think of these systems as guardrails on a mountain road. They don't make you a perfect driver, but they protect you when you're tired or the road is icy.

The most effective investors don't rely on superhuman self-control. They set up simple rules and automation so that emotional, impulsive decisions are hard to make.

Here's how to build your financial guardrails:

- Automate Your Investing: Set up automatic, regular contributions to your investment account. This removes the difficult choice of "when to buy." You'll keep investing through market drops (when fear says "wait") and resist overinvesting during surges (when excitement says "buy more now!").

- Write Down Your Plan: Create a simple investment policy statement. In a calm moment, write down your goals, risk level, and basic rules for rebalancing. When the market gets stressful, this written plan acts as your anchor, reminding you of what your clear-headed self decided.

- Choose Simple Over Complex: A complex strategy with many moving parts invites constant tinkering. A simple portfolio—like a mix of low-cost index funds—requires few decisions and very little maintenance. Its greatest strength is that it's boring, removing the temptation to make emotional "improvements."

The Shift in Identity: From Market Analyst to Self-Manager

Beginner investors often define their success by their ability to predict markets. They study charts, follow economic news, and seek insights that might give them an edge. This approach places them in competition with millions of other investors and analysts, most with similar information.

A more productive shift occurs when we redefine the challenge. Rather than asking, "What will the market do next?" we learn to ask, "How might my own psychology mislead me in this situation?"

This changes everything. The market becomes not a puzzle to be solved, but an environment to be navigated with awareness of our own tendencies. Success is measured not by outperforming indices in the short term, but by adhering to a sensible plan over the long term.

This perspective is humbling but empowering. It acknowledges that we cannot control external events, but we can develop awareness of our internal reactions. It recognizes that the most dangerous moments are not when markets move against us, but when we lose touch with our own carefully considered principles.

Practical Recognition: Learning Your Personal Patterns

Before we can build effective guardrails, we must understand where we are most vulnerable. This requires honest reflection on our past decisions.

Take a quiet hour to review your own investment history. Look for patterns. Did you sell during the market decline of March 2020? Did you increase your allocation to technology stocks in late 2021 when everyone was discussing their gains? Did you hold excess cash during periods of optimism because you were waiting for a better entry point?

These patterns aren't failures; they're data. They reveal your personal psychological triggers. One investor might be particularly susceptible to fear of missing out, leading them to chase trends. Another might be especially loss-averse, causing them to sell prematurely. A third might be overconfident after periods of success, leading them to take excessive risks.

Once you recognize these patterns, you can design specific countermeasures. If you tend to chase performance, you might implement a rule that you never buy an asset that has risen more than a certain percentage in a short period. If you tend to sell during declines, you might establish a policy that you never sell during a market correction without waiting a predetermined cooling-off period.

The goal isn't perfection. The goal is progress. Each time you recognize an emotional impulse and choose a different response, you strengthen your ability to do so again. You're not eliminating your emotions—you're developing a more mature relationship with them.

Conclusion: The Journey Toward Self-Awareness

The message of this tutorial is ultimately hopeful. The fact that our greatest investing challenges originate within ourselves means they are subject to our influence. We cannot become different people, but we can become more aware versions of ourselves.

This journey begins with compassion rather than self-criticism. Emotional reactions to financial uncertainty are not character flaws; they are expressions of our shared human nature. The investor who panics during a market decline is experiencing the same neurological responses that kept our ancestors safe from physical threats. There is nothing wrong with them—their brain is simply operating according to its ancient programming.

The path forward, then, is not about fighting our nature, but about understanding it and creating conditions in which it can coexist with our long-term financial well-being. It's about recognizing that the sophisticated part of investing isn't stock selection or market timing—it's the quiet, ongoing work of self-management.

As we continue in this series, we will move from understanding these psychological challenges to building practical systems that address them. We will explore specific structures, rules, and frameworks that successful investors use not to eliminate emotion, but to prevent it from making their most important financial decisions for them.

The first step, however, is this simple recognition: the market will do what it will do. Our reactions are what we can learn to understand and guide. In that shift of focus—from external prediction to internal awareness—lies the possibility of not just better investment returns, but a calmer, more thoughtful relationship with money itself.

For in the end, the most valuable return any investor can earn is not merely financial growth, but the quiet confidence that comes from knowing they can navigate uncertainty without becoming its victim. That confidence is built not by mastering markets, but by coming to know oneself with clarity and compassion.

About Swati Sharma

Lead Editor at MyEyze, Economist & Finance Research WriterSwati Sharma is an economist with a Bachelor’s degree in Economics (Honours), CIPD Level 5 certification, and an MBA, and over 18 years of experience across management consulting, investment, and technology organizations. She specializes in research-driven financial education, focusing on economics, markets, and investor behavior, with a passion for making complex financial concepts clear, accurate, and accessible to a broad audience.

Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes only and should not be interpreted as financial advice. Readers should consult a qualified financial professional before making investment decisions. Assistance from AI-powered generative tools was taken to format and improve language flow. While we strive for accuracy, this content may contain errors or omissions and should be independently verified.